Book Review: Adrian Miller’s Black Smoke

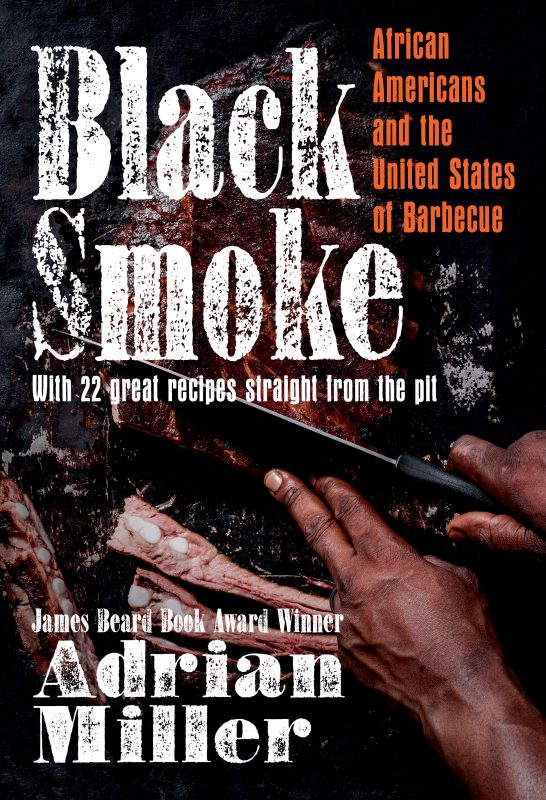

Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbecue

by Adrian Miller, The University of North Carolina Press, 2001,

301 pages, $30.00 USD/$40.00 CDN

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2021/2022 print issue of Quench Magazine. Subsequent to the book review originally being published, Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbecue won the 2022 James Beard Award for Reference, History, and Scholarship.

Just as a good piece of barbecue takes some time to cook, Adrian Miller’s Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbecue is going to be simmering in the minds of readers for some time to come.

Along with the Netflix docuseries High on the Hog, Black Smoke is a necessary corrective to the way in which African American pitmasters have been written out of their own food history. An engaging, intensely researched, and breezily written account tracing barbecue from Indigenous cooking techniques through to the current generation of pitmasters, Black Smoke has also kicked up conversations among those who have devoted their lives to the art of ‘cueing. In lieu of a standard book review, Quench reached out to a couple of pitmasters to ask their opinion of the book.

Quench: How did you feel when you read the book?

Lonnie Edwards, Ribtown BBQ , Los Angeles CA: I was just jumping up and down, like, wow, this is incredible. It was a long time coming, a book about the culture that really did all the barbecuing. I’m a California kid but my roots are southern, so I’m very lucky that I was raised around a lot of southern people and I understand where the roots of this culture comes from. In my opinion, other than people like the Native Americans who would have cooked on a stick over an open fire, modern barbecue comes from African Americans, particularly slaves. It’s all in the book.

Michelle Wallace, Gatlin’s BBQ, Houston TX: It definitely made me feel proud to be in this particular area within the culinary world. It really showed the importance of barbecue, and how it affected food within our culture. It’s so major. I mean, he covers the evolution of it all, from cooking over a live fire, coals and wood, from where it started to where it is now.

Quench: If you were to read about barbecue in the mainstream you’d see a monoculture where white people are the arbiters of quality. As Miller points out, that ignores the people who have actually progressed the art. There’s also a dismissal of history, whether intentional or not, explaining why barbecue developed as it did.

Edwards: I know what he means, I’ve had people tell me that my food is “not competition style.” My people weren’t cooking this food for any damn competition. They were trying to eat. That’s how this all came about. The guy who was telling me about “competition style barbecue” looked at me like “oooh.” He didn’t understand that the food my ancestors got was scraps that was thrown out. It was the roughest, toughest part of the pig, and they had to cook it down to where they could eat it. That’s why Black people like to eat meat falling off the bone. There’s a lot of history about the whole thing that they don’t get, and it’s in the book.

Wallace: I know what he means, though I came up differently. I was classically trained in the French brigade, I studied in China, then I eventually ended up in Texas barbecue. The book really covers a bit of the range of barbecue. I mean, there’s just so many similarities across the board when it comes to smoking and grilling meats over live fire. It’s almost just like a soulfulness that translates from culture to culture, you know?

Quench: Though in this case the translation is flawed; it would be like if America took credit for the invention of ramen.

Edwards: I’ll be honest, it’s true. I’m not sure if white Americans want to ignore the role that African Americans play in the history of barbecue or if they just don’t know or want to know. I just scratch my head at all of these barbecue organizations and groups and it’s all non-Black. It’s like we don’t exist.

Quench: Michelle, was there a part of the book that you really enjoyed?

Wallace: Definitely. He mentions that barbecuing and smoking were a way for Black people to build businesses at a particular time. I was enamored of that because I work for a family business and can relate to that. Selling food is a means to an end, whether in our culture or beyond our culture, and there’s something about him writing about African American entrepreneurs in the barbecue business that really grabbed me.

Quench: Final thoughts, Lonnie?

Edwards: Now that it’s getting out there with the book and other things it’s (the history) not going to ever get buried again. They can try to bury it and push it to the side, but it’s not going to happen. I’m glad people are talking about it now, it’s very personal to me and hopefully things will continue changing for the better.