One More Time

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2021 print issue of Quench Magazine.

At first, Alan Boyd was simply mesmerized by the stories.

MINGLING AT A NETWORKING GET-TOGETHER IN LONDON run by English TV presenter Steve Blacknell, the Canadian-born guitarist and producer found himself pulled into a musical deep dive as veteran bassist Mo Foster recounted anecdotes about his time as a first call studio musician and sideman for the likes of Jeff Beck, Ringo Starr, and Phil Collins. Not only was Boyd intrigued by the recollections, he was also curious. A longtime musician and music fan, Boyd wondered: why had he never heard of Foster before?

“These were fascinating stories about the people he knew and worked with,” recounts Boyd, director of One More Time, an upcoming documentary on Foster and other session musicians from the busy London scene of the ‘60s through to the ‘80s. “Hanging out backstage at a gig talking to Ringo when Eric Clapton walks up to chat with him, that kind of thing. He knew everyone.”

That’s because Foster was part of a small but respected crew of session musicians who came into their own during the first wave of British rock, eventually fulfilling much the same function in London as The Wrecking Crew in L.A., the Swampers in Muscle Shoals, or the Funk Brothers at Motown in Detroit. Unlike the other assemblages, all of whom were eventually celebrated in print and in film, Foster and his compatriots had somehow snuck under the radar, never even acquiring a nickname.

At the time Boyd was initially chatting with Foster he was riding high personally, securing a music publishing deal after composing the score for a 2009 star-studded BBC mini-series remake of The Day of the Triffids. This did not last long, as Boyd discovered the vagaries of the industry he was working in.

By 2013, his career in stasis, Boyd began casting around for something new to do.

“That’s the point where I turned to Mo and said, ‘you know, we should get your stories down and turn this into a film.’ He said ‘oh, well, you should talk to my friends (guitarist) Ray Russell and (drummer) Clem Cattini.’ It became this thing where he told two friends and they told another two friends, and it started growing. I was learning as I went along, and it sort of exploded my North American idea of how the British rock scene developed, that it really wasn’t around until The Beatles and the original British Invasion bands.”

Foster, Russell, and Cattini patiently brought the new director up to speed on the pre-Beat-les history of Britain, from the John Barry Seven (which featured a young Russell) to Cliff Richard, The Tornadoes to Johnny Kidd & the Pirates (both anchored by the solid drum work of Cattini). Boyd started recording the interviews with a digital camera using a simple setup, making use of skills he’d picked up working on various television productions since moving to London from Vancouver, B.C., in 1994. In response to Boyd’s tenacity, the three studio musicians used their contacts to bring in peers like Cliff Richard and Donovan for more interviews, and Boyd began to feel he was onto something.

Madeline Bell

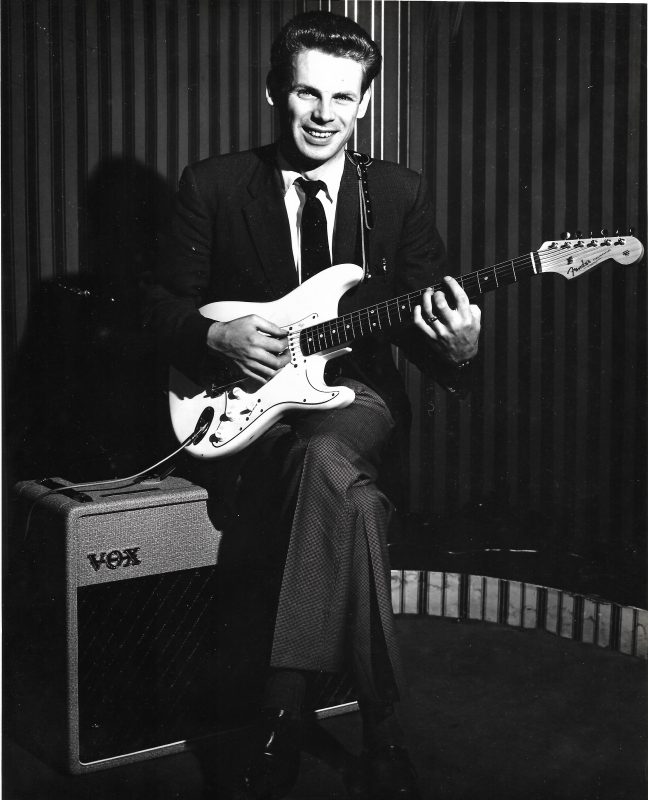

Vic Flick

“You could see the story coming together,” says Boyd, who went through both a serious inner ear condition and a heart attack while in the midst of putting the film together. “We looked into people like keyboard and Ham-mond player Alan Hawkshaw, who ended up doing all of this library music that’s becoming hip. A track that Alan wrote called New Earth was sampled by Jay-Z for his song Pray, and a sample of the song The Champ that he played on (with The Mohawks) is all over tracks by Salt-N-Pepa, Eric B and Rakim, and MC Hammer. There’s a whole generation of hip-hop producers that are very aware of Alan, Mo, and all of these studio guys.”

In a sense these hip-hop stars were reflecting back music that the London crew were assiduously learning from African American musicians over the radio during the earliest days of rock ‘n’ roll.

“I was immensely jealous hearing American musicians talk about the stations they grew up with,” laughs Foster. “We had the BBC, and at the time that was fucking awful. They just played the worst drivel. The only thing that saved us in the ‘60s was a station called Radio Luxembourg, which we could hear if we were in the right spot at the right moment. They played all of the good stuff we wanted to hear, but it would fade off all the time.”

They must have learned well. According to Boyd, when such heavy hitters as the Jackson 5 came to town they would request their favourite players among the extended crew.

“Michael Jackson was like, ‘oh yeah, hey Clem, how’s it going?’ They all knew these guys and admired them. They had the feel and they played everything. They’d do jazz sessions in the morning, then maybe a film score, and then at night, pop, or country, or rock. In America you’d have to go to different areas for each style.”

Some notable members of the revolving crew of musicians, like composer Hans Zimmer, managed to attain name recognition. Best known for scoring such

films as Gladiator, The Lion King, and the Dark Knight Trilogy, Zimmer (who moved to London from Germany as a teenager) started out as a synth player in various new wave bands, including The Buggles, before making the leap to television ads, jingles, and movie scores. It was through his ad work that he eventually made his way to Hollywood along with such London-based directors as Ridley Scott.

“At that time, London was the place to go for film music,” Boyd notes. “That’s where the best (music) readers were, as well as some great studios. Now L.A. has got some fantastic rooms as well, but London had places like Trident, or Pye, where Bowie used to record a lot. There was Abbey Road, where the Beatles recorded, and which had a bigger room where they did a lot of the film scores. There were just so many fantastic sounding rooms.”

Zimmer and his peers were genre agnostic, working with Motown artists, country artists, jazz and rock artists. This meant they had the facility to move amongst such musicians as John Barry, Georgie Fame, Lou Reed and the Bay City Rollers. According to Foster, Parisian producers of the ‘70s went out of their way to use the London crew because of their innate “feel.” They were adaptable but often unacknowledged, unlike Glen Campbell and Hal Blaine of The Wrecking Crew, or Charlie Daniels and Jerry Reed, who broke out to huge success after time spent as members of the Nashville Cats.

“There’s the guitarist Big Jim Sullivan, who was one of the real forces in music and unfortunately he’s passed away (in 2012), so we never got a chance to talk to him,” Boyd laments. “That guy was on so many hit records (like Thunderclap Newman’s Something in the Air and The Walker Brothers’ The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore). He went to America in the ‘70s and was part of the Tom Jones TV show; he was also on an episode of Space 1999 playing guitar in this sort of futuristic setting.”

Sullivan’s name may not roll off the lips like Jimi Hendrix, but in the industry of the time there was nobody more highly ranked. He gave lessons to Ritchie Blackmore of Deep Purple, worked with The Who, and palled around with Elvis. Eventually he formed his own band called Tiger, though he continued playing sessions and sideman gigs with the James Last Orchestra and the post-Grease phenomenon that was Olivia Newton-John.

“They weren’t always playing with the same people,” says Boyd, “they were moving around, and every time they walked into a session, they had to look and see who they were playing with.”

Foster chimes in. “I’d record in Colorado, or Canada, or the West Country (in England),” he says “We were all over the place.” When back in London they never lacked for gigs.

“The good music directors would start to know who to put with who on a certain session,” Boyd says. “Like bringing in Herbie Flowers to play bass with Lou Reed on the Transformer album

with Clem Cattini (who played on over 40 UK number 1 singles) on drums.”

The filming is done but the story continues. As of this writing, Boyd and his producer Christine Cowin are sending around rough edits of One More Time in order to secure more financing to clear the rights to the music. As Boyd notes, it doesn’t really work without the necessary Beatles, Bowie, or Serge Gainsbourg song at the right place. Still, Boyd feels as though they’re nearly there.

“We’ve got some great interest coming from some of the major broadcasters, but yeah, we’re in that final push to get the funding. We’re talking about some of the biggest tracks of that era that we’re looking to get into the film, and that means negotiating some of them down in cost. But, you know, at the moment I’ve got a hard drive with a film that I think is really good on it, and we’re bringing in an editor with a lot of music documentary experience to make the next cut. We’re so, so close to getting this done and I’m feeling really good about it.”

Feature Image: Brian Bennett and Ray Russell | Photo Credit: Chris Tubbs Photography