Regenerative Organic Pioneers

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2022 print issue of Quench Magazine.

When the creators of a new farming regimen called “regenerative organic” went looking for a winery to be the first to join, naturally they approached Tablas Creek Vineyard.

Tablas Creek, organic from its inception, imported most of the high-quality clones of Rhone grapes now used in California. The vineyard built a nursery to grow them, and rather than hoard for competitive advantage they instead shared them widely so Rhone-style wines would improve. For weed control and fertilizer, Tablas Creek uses a large herd of sheep and a flock of chickens.

Based in Paso Robles, one of the most drought-prone areas of California, the winery adjusted its planting density so that even young vines don’t need to be irrigated. In addition, it plants heirloom fruit trees every year for biodiversity and to give its employees fruit to take home. Why wouldn’t Tablas Creek be the first to go regenerative organic?

“When they came to us, our first thought was, we’re already doing organic and bio-dynamic certification,” says Tablas Creek general manager Jason Haas. “Another certification? Seriously? We were already doing so much paperwork. But the more we looked at it, we thought it would be the gold standard for farming.”

“Regenerative” is the new buzzword for farming. The base concept is that farmers can help slow climate change by growing plants that move carbon dioxide into the soil. Thus the goal is different from other well-meaning agricultural practices. I like to sum it up this way: organic is consumer-focused, while biodynamic is process-focused. Sustainable is business-focused (which is why big businesses love it). Regenerative organic is, in its infancy, eco-system-focused. For Haas, that was appealing.

“Regenerative organic separated the soil health pieces of biodynamic from the mystical pieces,” says Haas. “That’s one of the things I have really high hopes for about regenerative organic. It doesn’t have that baggage attached to it. Organic is a list of things you can’t do. If you don’t use certain chemicals you can be organic. Biodynamics is a process by which you create a healthy ecosystem that eliminates the need for chemical inputs, plus some pixies and fairy dust stuff. Regenerative organics is, how do you change your farm into an engine for positive change for you and your workers and the people who buy your wine? The soil health pieces of regenerative organics come directly from biodynamics. The difference is that if you are farming through regenerative organics, you have to measure the carbon content of your soil. It’s more results-based, whereas biodynamics is process-based.”

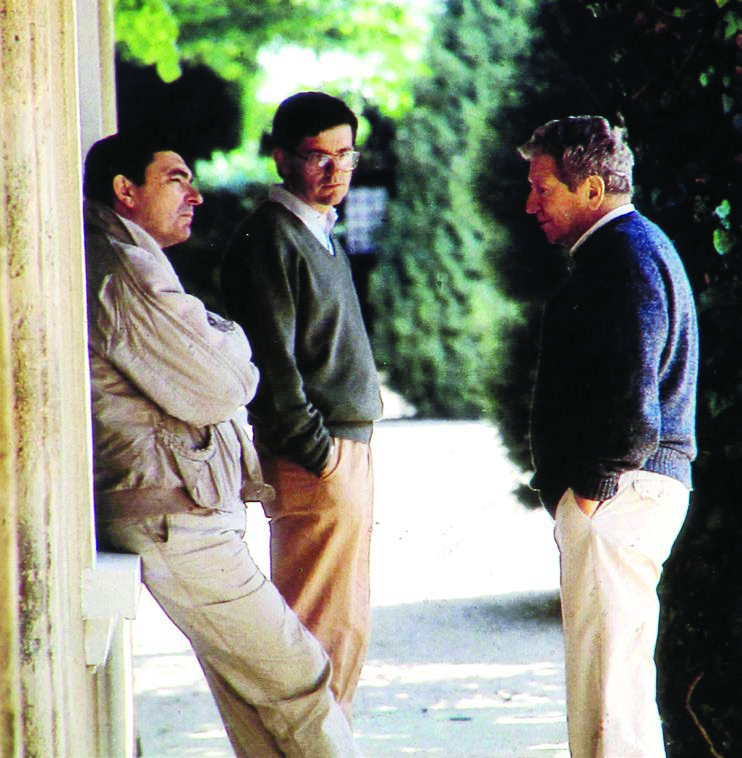

Haas and Tablas Creek winemaker and vineyard manager Neil Collins both made time for me over the winter holidays to chat about regenerative organic viticulture because, both said, it’s important that this story be written.

“It’s more interesting to me to speak to you in the hope that another farmer will read it and go down that road than that a consumer will read it and buy a bottle of wine,” Collins states.

Don’t discount the power of a pulpit. In December 2021, the much larger Fetzer Vineyards became the second winery to be certified regenerative organic; that makes it a movement.

Being the regenerative organic pioneer among wineries fits perfectly in the history of Tablas Creek. It was planned ambitiously from the start by its founders: Robert Haas, founder of the US wine import company Vineyard Brands, and the Perrin family, who own Château de Beaucastel in France’s Rhone Valley. Jacques Perrin started farming organically in the 1950s before the concept even really existed.

“The way that chemicals were being pushed just felt wrong to him,” Haas says. “He did a year without any of the chemicals and was just blown away by how much the wines tasted like Beaucastel compared to the previous decade. There was no certification then. I don’t even think there was a word for it in French.”

Haas says his father and the Perrin family agreed that they would plant organically. They looked all over California for shallow, rocky limestone soils like those of Beaucastel, as well as that winery’s hot-summer-days, cool-nights climate. The best match was found in 1989 in what is now the Adelaida District west of Paso Robles.

They were unusually patient for a startup, even for an estate winery. Deciding not to work with the Rhône grape clones then available in California, they instead imported cuttings of nine varieties from Beaucastel and waited three years for them to clear quarantine. They couldn’t begin planting on their property until 1994.

“The clones that were in California, particularly Grenache and Mourvedre, at some point had been planted for productivity and not high quality,” Haas notes. “Grenache in the central valley was the main ingredient in Gallo Hearty Burgundy. We didn’t want to limit ourselves to the clones in California and wonder later if that’s why things were different.”

Robert Haas had a vision, and it extended to more than just the right clones.

“I tended to get sent to vineyards to work for the summer if I hadn’t found another job,” his son says. “There was a long game going on that I wasn’t aware of at the time. I spent two summers working at Beaucastel getting to know the next generation of Perrin kids. I thought the idea was for me to work on my French. My dad did a good job of holding the door open for me to come into the family business, but without me feeling forced into it.”

Jason Haas joined the family business in 2002. His father and the Perrins had overestimated how easy it would be for an unknown winery to sell blends of little-known grape varieties; they had a warehouse full of unsold wine. Jason took over the marketing at first and became general manager a few years later. During that time, the winery imported seven more grape variety clones: all the remaining Chateauneuf varieties for a total of 14, plus Viognier, Marsanne, Tannat, Vermentino and Petit Manseng.

If you visit Tablas Creek, don’t skip the opportunity to buy wines in the shop. Tablas Creek makes single-variety wines out of some of these rare French grapes, and in at least one case (Vaccarèse) is believed to make the only single-variety version in the world.

The winery was organic from inception, but going biodynamic happened after a visit to Grgich Hills in 2009. Grgich Hills wine-maker Ivo Jeramaz was an early advocate for biodynamic viticulture in Napa Valley. It was a drought year, but Grgich Hills’ vines looked vibrant. Robert Haas announced on the way home that Tablas Creek would try it.

“Bob, Jason’s dad, is like that,” Collins says. “I was saying, let’s think about this or that and he said, let’s just do it.”

Part of biodynamic theory is to have a whole working farm, with animals.

“We started with about a dozen sheep that an employee happened to have,” Collins recalls. “We brought in a couple donkeys to guard them from predators. I didn’t want to have dogs because of dogs biting people. Don-keys are guarding animals. They can be pretty effective against coyotes; not so much about mountain lions. But maybe one donkey would have been better because we had two donkeys and they formed a donkey team and didn’t care so much about the sheep. We just lost too many sheep to mountain lions. We lost 26 sheep one year. We had to kill a mountain lion because it kept coming back. From my standpoint, having sheep to graze our vineyard isn’t sustainable if we have to kill the local wildlife. We investigated dogs and got two incredible Spanish mastiffs. We lost one sheep that year and haven’t lost a sheep since.”

The main purpose of the sheep is to eat grass and weeds, turning them into fertilizer, but Tablas Creek also has a side business selling biodynamically raised lambs to local restaurants.

The regenerative organic conversion started with a biodynamic lamb and wine dinner Collins hosted in Ventura, an affluent suburb of Los Angeles. One of the guests was Yvon Chouinard, founder of the clothing company Patagonia.

“He didn’t want to talk about wine. He wanted to talk about farming,” Collins said. “He said the only way we’re going to reverse climate change is through farming. I wasn’t a Patagonia disciple. So many people I work with, all they wore was Patagonia. For me, it’s a bit expensive. But he was infectious and his dedication to farming was impressive to me. Talking to him got that ball rolling, and now here we are with the first regenerative organic vineyard in the world.”

Because the vineyard was already bio-dynamic, Collins said he hasn’t yet seen an impact on the vines per se.

“I can say that our wines have been constantly improving over the years since the bio-dynamic, and since the regenerative organic the wines have gotten better and better,” Collins said. “The original goal of Tablas Creek was to make wines that are of a given place. The wines keep improving. We like the wines more and more. Is it the effect of spraying quartz on the Syrah? I don’t know. But I know the Syrah tastes better than it did 10 years ago.”

Regenerative organic also has requirements for farm worker welfare, and Haas said he has already seen the benefit of that.

“You have to train your crew on their rights as farm workers,” Haas said. “You have to set up a system where they can provide feedback. You have to pay them 10% above the living wage for your area. We have seen our vine-yard crew, many of whom have been here for decades, on weekends they bring their families out to see what they’ve been working on.”

Why not? They are pioneers.