This article originally appeared in the Fall 2021 print issue of Quench Magazine.

The tale of Oregon’s wine foundations has been recounted many times, but the story never gets old. It lends insight into the industry’s personality and serves as a reminder of how far the state has come in a short time.

Grapes were first planted in 1847, but Oregon’s burgeoning wine industry was nipped in the bud by prohibition. It wasn’t until 1961 that Richard Sommer established the first post-prohibition licensed winery in the Umpqua Valley. Shortly after, UC Davis graduates David Lett, Charles Coury, and Dick Erath made their separate ways to the Willamette Valley. They believed that the cooler reaches of Oregon were better suited for Pinot Noir than California despite being advised otherwise. The trio were soon joined by David and Ginny Adelsheim, Pat and Joe Campbell (Elk Cove), Dick and Nancy Ponzi, and Susan Sokol and Bill Blosser.

Oregon’s original pioneers were united by their unorthodox aspirations. “In the ‘70s and ‘80s, we were so heavily reliant on each other,” recalls David Adelsheim. “We were broke and had no idea what style of wine would be appropriate in Willamette so we tried to forge a common style.” Through a collaborative spirit they crafted individualist wines.

It was David Lett’s 1975 Eyrie South Block Reserve Pinot Noir that put Oregon on the international radar when it placed in the top 10 of the Gault-Millau French Wine Olympiades in 1979. Even with accolades, Oregon wine was not an instant success. “The biggest problem in the ‘80s and early ‘90s was not being taken seriously as a wine region,” continues Adelsheim. Wine drinkers didn’t start embracing Willamette’s cool climate Pinot Noir until the turn of the century. There has since been a boom in growth – from 139 wineries in 2000 to 908 in 2019. Nevertheless, Oregon remains a region of boutique producers.

Besides making a name for itself with Pinot Noir, Oregon has distinguished itself as a leader in sustainability. In 1997, a handful of Oregon winegrowers established LIVE. Short for Low Impact Viticulture and Enology, LIVE certification has now been awarded to almost 300 wineries and vineyards. Producers were also early adopters of Salmon Safe which prohibits pesticides and protects fish habitats. Sokol Blosser was the first to be certified in 1996. “My parents have always had a good-for-the-earth organization but what that has meant has changed as years go by,” says winemaker and Co-President Alex Sokol Blosser.

The latest uptick is in wineries getting B Corp certified, a third-party organization that considers the triple bottom line of people, planet and profit. “It holds us accountable for all aspects of our business and sheds light on what we can improve,” Sokol Blosser explains. Oregon’s largest wine producer, A to Z Wineworks was the Willamette’s first B Corp certified winery in 2014. Oregon now boasts eight – apparently the largest number within any region around the world.

Oregon’s wine future is now securely in the hands of the next generation. Some are direct descendants of Oregon’s founding figures while others were mentored by them. Before establishing her eponymous label, Kelley Fox worked for David Lett at The Eyrie Vineyards. “They opened the door and set a very high bar and over time the general ethos seems to have been shared with those to follow,” she says of Lett and his peers. While Fox doesn’t own vineyards, she personally farms the plots she buys fruit from, employing biodynamic practices. As for winemaking, additives are essentially limited to minimal sulfur, and she has completely renounced new oak. Her wines speak to Oregon’s idiosyncratic beginnings.

While Pinot Noir is firmly cemented as Oregon’s flagship (Pinot Gris is a distant second), Chardonnay is on the rise. This grape got off to a rocky start as Oregon’s original clones came from California. In the early ‘90s, David Adelsheim was able to bring in earlier ripening Dijon clones which have smaller clusters and berries and are better suited to a cool climate. “They really helped change the dynamics of Willamette Valley Chardonnay,” says Jesse Lange at Lange Estate. His parents have been making Chardonnay since 1987. “Now the vines are mature, we’re a three-decade overnight success,” he jokes.

The challenges facing Oregon’s winemakers today are vastly different from those encountered by their predecessors. “The most obvious is climate change,” says Bree Stock, Master of Wine and Education Director for the Oregon Wine Board. She points to increasing heat waves and drought conditions and the implications for Oregon’s dry-farmed areas as well as water availability in irrigated zones, not to mention the style of wine produced.

To help mitigate the effects of climate change in the vineyard, Mimi Casteel is championing regenerative agriculture. Daughter of Bethel Heights’ Ted Casteel and Pat Dudley, she set out on her own in 2015 to establish Hope Well Wine and Vineyard equipped with a master’s in Forest Science and experience as a botanist and ecologist. She has honed farming techniques that emphasize soil health, biodiversity, cover crops and no tillage in order to improve water retention and sequester carbon.

Regenerative farming is gaining steam. It was the focus at both the 2019 and 2020 Oregon Wine Symposiums and in June 2021, Troon Vineyard in Southern Oregon’s Applegate Valley was the state’s first winery to receive the newly established Regenerative Organic certification. Truth be told, this isn’t a new concept. David Lett established The Eyrie Vineyards on these tenets in 1965 and his son Jason has continued this legacy.

Jason Lett has also adopted his father’s innovative nature and planted alternative varieties such as Trousseau, Chasselas Doré and Melon de Bourgogne. According to Stock, this is a simmering trend as growers look to diversify their plantings and winemakers seek to experiment with different grapes. “The beauty of Oregon is that there is still much plantable land available, and no restrictions surrounding varietal diversity and wine style,” she says.

Rather than a tsunami, Oregon’s evolution comes in slow, steady waves from well-established foundations. And while a spirit of pioneering runs deep, so do collaboration and sustainability. Oregon is in it for the long game.

Wines

Erath Pinot Noir Rosé, 2020, Oregon ($23)

Owned by Chateau Ste Michelle since 2006, Erath produces a line of accessibly priced wines blending estate and purchased fruit from throughout Oregon. The rosé is on point with its pale pink hue and decidedly dry palate. Clean, steely and refreshing with watermelon, citrus and pretty floral accents.

Left Coast ‘The Orchard’ Pinot Gris, 2019, Van Duzer Corridor ($28)

Established in 2003, Left Coast was the first winery in the windy Van Duzer corridor and instrumental in the zone achieving AVA status in 2019. Restrained and leesy, the Pinot Gris offers fresh cut apple and pear. A concentrated fruity core is countered by bitter grapefruit pith and vibrant acidity.

Domaine Drouhin ‘Arthur’ Chardonnay, 2018, Dundee Hills ($90)

Made from Dijon clones, this is a testament to the potential of Chardonnay in Oregon and a tribute to its Burgundian heritage. Hints of butter and lemon curd lead to a creamy palate with apricot, pineapple and a subtle but lingering nuttiness. Elegant and deftly balanced in its proportions.

Chemistry Pinot Noir, 2018, Willamette Valley ($30)

Bill Stoller’s newly launched Chemistry label sources fruit from growers across the Willamette Valley for an attractive and affordable package. It’s plump and fresh with dark black cherry, crushed florals and a playful touch of bubble gum. Fine ripe tannins cleanse the mouth and lead to a minty finish.

Sokol Blosser Estate Pinot Noir, 2017, Dundee Hills ($40)

Pronounced scents of smoke and leather infused with clove and cinnamon make for an exotic nose. Medium weight yet plush with a mix of ripe summer berries framed by sweet wood tannins. This offers immediate appeal. Salmon Safe, organic and B Corp certified.

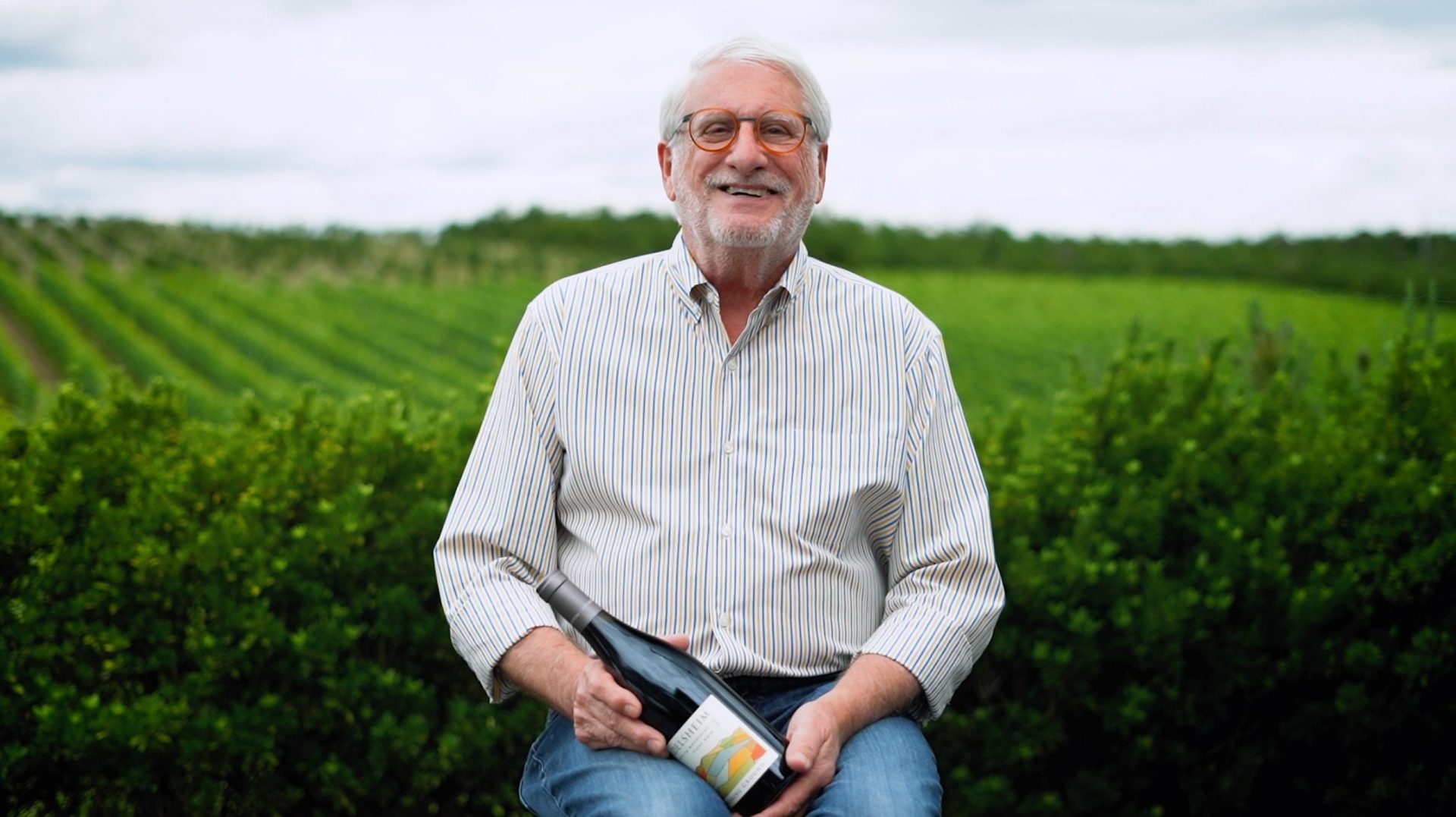

Willamette Valley Vineyards Estate Pinot Noir, 2018, Willamette Valley ($40)

Launched by Jim Bernau in 1983, WVV was the first ever crowdfunded winery. It was also a founding member of LIVE as well as Salud! which supports free and accessible medical care for vineyard workers. The estate Pinot exudes aromas of sweet herbs, coconut and blackberry. Silky and layered, the palate brings in cola and oak spice. Lots to chew on but buoyant and light on its feet.

Adelsheim ‘Breaking Ground’ Pinot Noir, 2016, Chehalem Mountains ($70)

A complex and intriguing mix of dill, wet earth, mushroom and mineral with distinct cherry overtones. Oak is integrated and polished tannins are suede in texture sticking appropriately to the finish. Besides writing Oregon’s wine labeling regulations, David Adelsheim drove for recognition of several Oregon AVAs. He sold the winery in 2017 to partners Lynn and Jack Loacker.

Domaine Serene ‘Evenstad Reserve’ Pinot Noir, 2017, Willamette Valley ($90)

Grace and Kevin Evenstad were among a surge of early believers settling in the Willamette Valley in 1989. One of the first wines they produced, the Reserve Pinot Noir is a blend of estate vineyards. It is noticeably toasty up front with chai spice and caramel ceding to earthy nuances. Flavours of sumptuous cherry and dark raspberry are interwoven with cedar and brightened by energetic acidity.