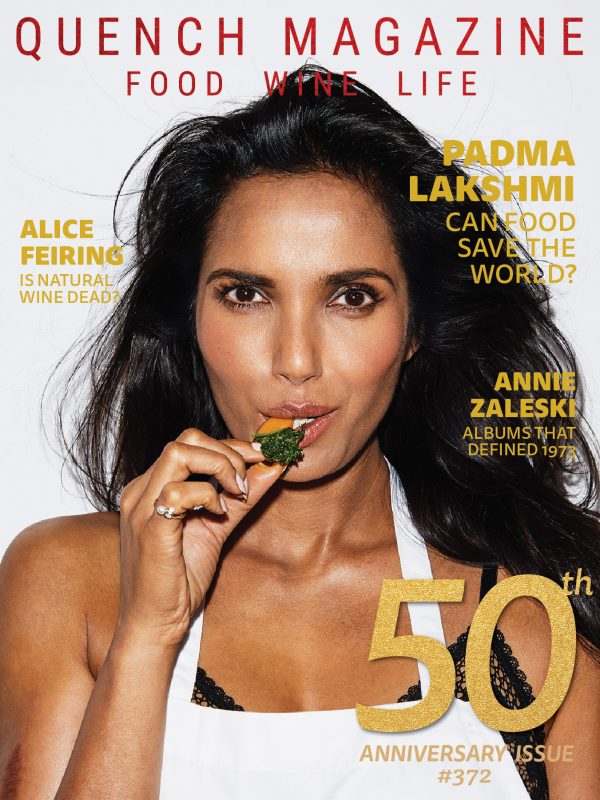

Can Celebrities Influence Systemic Change through Food?

This article originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2023 print issue of Quench Magazine.

In 1999, Padma Lakshmi began her public culinary journey by writing Easy Exotic: A Model’s Low-Fat Recipes from Around the World. Her main goal was to show people a healthy way to lose weight while still exploring global flavors. Nearly a quarter of a century later, Lakshmi is the host of Taste the Nation and has grown a prolific, multifaceted (cookbooks and television shows), award-winning platform that is changing the way Indigenous and immigrant food stories are told. We spoke with Ms. Lakshmi to find out more about why her work remains undone.

The following conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

What got you first interested in food?

I think I was always interested in food because my palate is very sensitive. So, from a very young age, like even as a late toddler at three or four, I was climbing the pantry shelves … in my grandma’s house … trying to taste all the different things she had, including some very spicy pickles and chutneys. Then as I grew, I would always hang around in the kitchen and I was just absorbing everything that was cooked by my grandmother or my aunts or my mom. We didn’t go out to eat to fancy restaurants, or even any restaurants regularly, other than maybe Chinese or Thai food, or pizza twice a month. So, I didn’t really know [culinary arts] was a profession, and I didn’t really start reading good food writing until I got to college … M.F.K. Fisher, Calvin Trillin, Nigel Slater, that kind of thing. I just enjoyed it. Calvin Trillin’s The Tummy Trilogy changed my life, and so did How to Cook a Wolf by M.F.K. [Fisher]. So, that is how my entry to food began.

How did your journey unfold after that?

[For] my first movie, I had to gain 20 pounds. After that, I needed to lose the weight in a healthy way. I’d never really been on a diet, so I just kind of made some alterations in my repertoire of recipes, and a book came out of that. That is how my [food writing] career got launched when I was around 28 years old. It was not my first career. If you had told me, when I was a teenager or even in college when I was studying for my theater degree, that I would be in food, I would have said: “Oh, no, I doubt that. That’s just for French white people, especially white men.” But, of course, now if you ask me today, after 20 years in the food industry, I would say that the most exciting food is what’s happening on the ground, at a grassroots level, in many mom-and-pop restaurants of various ethnicities.

Toronto, Canada is an exciting place specifically for that kind of food. I went to stay with my cousin, Arthi, in Markham, for example, which is a [Toronto] suburb, and there’s the Sri Lankan neighborhood, there’s the Thai neighborhood, there’s the Chinese neighborhood. It’s so fascinating. You can drive from one [neighborhood] to another within 10 minutes.

That first book was called Easy Exotic, right?

Yeah, and honestly … if you ask me now, I cringe at that title. But, in my defense, what I was trying to communicate with that title and that book is really the same thing that I’m doing now in my career. I’m trying to demystify dishes that we traditionally, in the established Western European canon, think of as the “other.” I’m trying to make them familiar. I’m enthusiastic about that kind of food because it’s the kind of food that I love to eat most on my own time. It’s not some moral thing that I need to take up as an immigrant. It is genuinely what I would be interested in even if I wasn’t paid to do it.

Do you feel like you have the same audience across the various platforms that you use?

I think my audience is as young as 12 or 14 years old, and as old as someone in their 80s. I think they are different [audiences]. Things about my body of work touch different sectors of the population; I hope other immigrants or children of immigrants, or even [the] grandchildren of immigrants, who may not be Indian or even Asian, really can relate to the type of cooking [that] I’m doing. I don’t only do Indian food.

If you look at both my cookbooks, I have [traditional recipes], and I’m updating them, modernizing them, making them more approachable, because that’s what I do in my own kitchen. Gone are the days when we have four hours to prepare a meal. Everybody is working and trying to get home, wants to go to the gym, wants to help their kids with homework, wants to deal with the 15 emails they get after 7:00PM, you know? So, a lot of [cooking] shortcuts in our modern world are helpful because they make those recipes more accessible.

Is that the most traditional way to do things? No. Is that probably the version of the recipe that’s most likely to get made? Yes, in my opinion. And I’m always cooking for that working parent who, you know, is middle class or even working class. Maybe they took a vacation somewhere, studied abroad in college, or they love to go to that local Thai restaurant, but they never make those things at home because [those recipes are] intimidating. That’s my audience. My audience is not the audience that regularly goes to three Michelin-starred restaurants, right?

I’m very comfortable in the [fine dining] food world, but I gotta be honest. When I’m not being filmed, I probably go to those tasting menu type meals maybe twice a year. If I wanted to go more, I could. And I value that kind of food. I respect it. I understand the expertise, and almost culinary brilliance and patience it takes to achieve that high art of food, but it’s just not where my curiosity lies.

photo courtesy of Padma Lakshmi

50th Anniversary cover credit: Jennifer Livingston/Trunk Archive

Is it fair to say that you’re really advocating a kind of systemic change through food?

I have spent the bulk of my career in food on Top Chef, outside of my writing and other engagements. I have seen food trends evolve, but what I have also seen is that there’s a specific canon of Western European food rules that are propagated by mostly French culinary technique … [t]hat was the prevailing barometer by which people measured everything. But that is not how most of the world eats.

Over the years, I got a little tired of the same thing, and then the 2016 election cycle happened. I heard so much venom being spewed from Washington and [President] Trump and all that against minorities. There was this almost patronizing arrogance about who owns America and how did they come to own it. I started doing whatever I could to counteract a lot of that venom in the media that was coming out of people like Steve Bannon or Stephen Miller. I started working with the ACLU [American Civil Liberties Union] [and have been] for seven years now. It was through them that I learned about other marginalized and minority communities in America. From a grassroots perspective, [I] started talking to immigrants of all kinds. As I learned about their food, I wanted to do something artistic. That is how Taste the Nation was born, and it has been the professional highlight of my career.

What kind of feedback have you been receiving about the show?

I can tell you I was very pleased to get 100 on Rotten Tomatoes. [Laughs] I always thought hopefully it would happen as an actor, but I’ll take it. I’m very proud of the show. There was a beautiful article in UPROXX written by an Indigenous person [Zach Johnston] when the first season came out. That really was quite moving to me because, if you want to really talk about American food, then you can’t have

that discussion without featuring and investigating Indigenous native food[s] from the Americas, right? There was The New York Times piece by Tejal Rao [about the show] and she’s somebody I really respect and admire. I was very moved by that. There was also an article in The Atlantic. Those three big articles were very gratifying, because it’s one thing to feel very passionate and [have it live] in your head. It’s another thing, and nothing short of a miracle, that you actually get to make a show that you had in mind [and share it with others].

Was your vision a hard sell for the platform that ultimately aired Taste the Nation?

It wasn’t a hard sell for my partner, David Smith, of Part 2 Pictures, or for my own production company Delicious Entertainment. We got turned down by six or seven networks before we got to Hulu. And by the time Hulu said they wanted to speak to me, I was feeling quite demoralized. I thought maybe this is something that only I want to watch because everyone kept telling me that there were enough of these kind of travel shows. That I was trying to be [Anthony] Bourdain, and I was not trying to be Bourdain. Nobody could be Bourdain!

I just had such a specific view of the show that was born out of my personal experience and [the experiences of] many of the people in the communities that I grew up [around], whether they were Mexican or Filipino or whatever. I just thought, OK, maybe it [the show] is not a good idea. I concede that my tastes are not commercial or mainstream.

[After several failed pitches], every time Hulu came around, it was like, I’ll take the meeting, but I’m not leaving my desk. I literally pitched them the show in my pajamas [over Zoom]. And I have to say, they have been a fabulous partner to work with, and as an author, I could not ask for more.

What was the elevator pitch for Taste the Nation?

Taste the Nation, which takes its title as a riff from a political show on television here in America called Face the Nation, is a show that explores immigrant and Indigenous communities in America, that have often not been given the mainstream platform or spotlight that Western European foods and cultures are often given.

What would be your advice or how would you inspire somebody to get involved in making systemic change through food?

If you’re in the food industry, like if you’re a chef who’s hiring, I would say please go out of your way to recruit from communities that are not yours. That is to say, if you’re a French male, or if you’re a white male chef with a lot of power to hire, please go and hire in urban areas and where kids don’t even know that’s a career that’s available to them. Your food and your restaurant will be better because they’ll bring a whole different body of personal experience to your kitchen, and that diversity is good for your bottom line.

If you are a dean at any cooking school in North America, I would strongly urge you to look at your curriculum and make sure that you are teaching African American food or African diaspora food. Because Black people in this country are the ones who built southern cooking and it’s often swept under with one very big brush, but there are nuances that are easily traceable back to Senegal and Nigeria and Sierra Leone.

If you are not in the food business at all, I would say be mindful of where you shop and then just [approach it] from a fun kind of perspective with your children. Pick a country and look up the foods of that country, then go and get the groceries you need with your child in tow so that you can teach them about different communities through food, just like I do on the show. And it’s never too early to get your kids involved in the kitchen. I would say one of the biggest pieces of advice I can give to any parent is that if you want your kid to eat well, give them the gift of good food. The best thing you can do is to cook at home as often as possible, and as early as possible, as your kids grow [up]. A child who takes part in the preparation of their own food is more likely to eat healthy and eat more varied foods. And that can be as simple as a three year old shelling peas or breaking the ends off beans, or a five year old cooking vegetables.

What’s next for you in terms of something you want to highlight in the culinary world?

I have a few months now of downtime and, you know, Taste the Nation actually started as a book project and then it morphed into a television project. I still want to do the book because a book and a TV show are two different mediums and [I can] communicate different nuances with each. So my next project is … a cookbook, but I also want it to be a travelogue of everything I’ve learned that I didn’t have time for in the show to share with people. And I hope that that inspires other people, even if they can’t go on the journeys or travel to the places and embed themselves in the communities that I feature. Perhaps they can travel there with their families and the fork.

Adrian Miller is a food writer and recovering attorney who lives in Denver, Colorado. He served as a special assistant to President Bill Clinton with his Initiative for One America – the first free-standing office in the White House to address issues of racial, religious and ethnic reconciliation. Adrian’s first book, Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time won the James Beard Foundation Award for Scholarship and Reference in 2014. His most recent book, Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbecue, was published in 2021 and won the 2022 James Beard Award for the same category. Adrian is featured in the Netflix series High on the Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America.