This article originally appeared in the Winter 2021/2022 print issue of Quench Magazine.

Wine acquires its context through people, time and place, and there is currently no one more adept at giving context to place than Alessandro Masnaghetti.

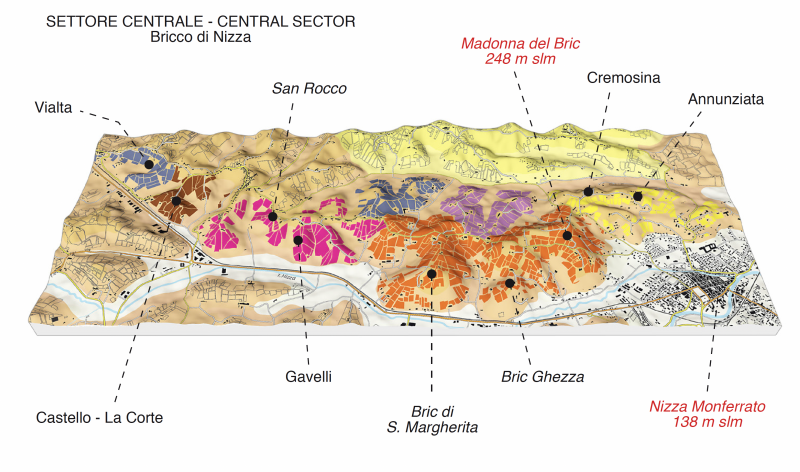

“A map is an instrument, a medium,” says Masnaghetti, whose name has become synonymous with maps. Through his company Enogea, he has drafted and published detailed maps of some of Italy’s most prestigious denominations and his accompanying commentary takes the viewer on a journey through the vineyards with him. They have become essential tools for wine professionals and are equally venerated by serious aficionados. The most celebrated are those of Barolo – so detailed that he has compiled not just one but two books that consider the region’s vineyards from every angle. The maps convey the natural features of terroir like soil, temperature, steepness and aspect of slope as well as which grape is planted where and ownership of each parcel.

The man behind the maps is just as multifaceted as the maps themselves, and as fascinating as the regions he charts. Before assuming that Masnaghetti was born with wine running through his veins, consider that he is originally from Milan. A hub of industry and finance, this northern Italian city is far more famous for fashion than wine. “My father drank really terrible wine. It was a spritzy red, acidic and bitter with green tannins.”

While this may have delayed his appreciation for wine, Masnaghetti muses that his father’s career as a technical draughtsman influenced his post-secondary pursuits. He studied nuclear engineering at Milan’s prestigious Polytechnic University, earning his degree circa the Chernobyl disaster of 1986.

Soon after, Italy passed an anti-nuclear referendum. Without a job in his field, Masnaghetti worked briefly as a general engineer, but his heart wasn’t in it.

He was, however, a budding epicurean. “I don’t really know how this passion was born. My family wasn’t interested in gastronomy at all.” He does recall amusing himself as a young boy by peering in the window of a pastry shop watching the bakers at work. As he grew up, dining out became a hobby. On a lark, he submitted some of his personal restaurant reviews to I Ristoranti di Veronelli, Italy’s counterpart to France’s Michelin restaurant guide. It was founded by the late, great Luigi Veronelli, one of Italy’s most renowned and influential food and wine critics.

“I didn’t expect a reply, and above all, I didn’t expect one from the boss.” Not only did Veronelli write to thank him, he invited Masnaghetti to lunch. When he arrived, Veronelli introduced him to Fattoria Zerbina’s Cristina Geminiani, who later became Masnaghetti’s wife. “We always say that it was Veronelli who introduced us, even though we had met a few days earlier at a wine tasting.”

Veronelli also asked Masnaghetti to write for his wine guide, which he did until 1996. He went on to become the first editor of the Guida Vini dell’Espresso and eventually created his own newsletter, Ex Vinis. “From the time I started working for Veronelli in 1990 until 2015, my principal activity was as a wine taster. The new generation knows me as a cartographer, and no one remembers

that I was a wine taster – of many wines.” In the golden era of L’Espresso, he was tasting 15,000 to 18,000 wines a year.

Masnaghetti supplemented his practical experience with courses on viticulture and oenology at the University of Bordeaux, sharpening his critical perspective. “When you visit wineries, you collect a lot of information, which can be contrasting. One of the best ways to put everything in order is to produce a map.” Spoken like a trained engineer.

The first wine region he mapped was Barbaresco in 1994. It was based on legal land parcels rather than actual vineyards. Alas, Masnaghetti was ahead of his time and his early maps were slow to sell. Still, he persevered, using whatever pictures were available, visiting each region to verify and draw in vineyards one by one. This painstaking work set him apart.

“My point scores weren’t as high as other journalists but the fact that I had this detailed knowledge of the territory helped me earn credibility with the producers.” He also made a point of visiting every winery within a zone, regardless of its repute. “I dedicate the same time and the same importance to each one. I did this as a wine taster and when I became a cartographer, it became even more important for me.”

As satellite imagery improved through the mid-2000s, so did the precision of Masnaghetti’s maps. However, they were still slow to catch on.

“Today everyone talks about crus and vineyards, but even just 10 years ago it was difficult for many producers to understand the value of these maps.”

Starting with Barbaresco and Barolo was natural as esteemed vineyards have long been recognized in the Langhe. Masnaghetti soon followed with Valpolicella, where the tradition of crus is also well-entrenched.

In selecting which regions to document, Masnaghetti balances his predilections with the economic reality. “Selling a book on Barolo or a map of Chianti Classico is easy – one of Taurasi, less so but the quantity of work would be identical.” As for Chianti Classico, it was in obvious need of a map, according to Masnaghetti. “The zone is extremely varied and complicated; it was too intriguing not to make a map.” In the same breath, he derived satisfaction from Montepulciano, which he describes as a more homogenous area.

“Sometimes simple work is more useful and beautiful than complicated work that you don’t succeed in translating.”

He has also ventured beyond Italy, partnering with Vinous’ Antonio Galloni to create maps for Napa and Sonoma – the latter due out at the end of 2021. He speaks fondly of the estates’ enthusiasm and willingness to collaborate while noting that geographical records of California lack the detail found in Italy. “This makes it more difficult to talk about the territory but at the same time, it makes the challenge more fun.”

It is clear that each project has been unique-ly gratifying on several levels. Masnaghetti expresses affection for the wines of Bolgheri and their connection to Bordeaux as well as admiration for the geology, describing it as intuitive to explain and understand.

“It is very ‘engineered’ but it is also a fantastic place. Even when you go in winter, as soon as the clouds disappear, there is a distinct perfume…”

Sadly, fragrances have yet to be captured by maps. Nevertheless, Masnaghetti has found a way to transport the viewer to the region of Barolo through his Barolo MGA 360 site. “When you see a map of a hill you can only imagine you are there, but when you see a photo taken with a drone that you can move, you are no longer just a spectator.” He recently launched a similar series for Chianti Classico and Barbaresco, which should be unveiled within the year.

The beauty of this new generation of maps is their ability to convey the landscape, which has become Masnaghetti’s great objective. “Rarely does the landscape have a direct influence on the style of the wine but it does explain a lot.” A change in landscape, such as different vegetation suggests a change in soil or microclimate, and it is these factors that contribute to shaping the wine.

Masnaghetti illustrates his point using the villages of Barolo. He describes the hills of La Morra as softer and rounder than those of Serralunga, which are much steeper.

The visual difference is obvious to anyone who casts an eye on the landscape.

According to Masnaghetti, the key to this difference is the soil: in Serralunga, there is more sand, thus more erosion resulting in steeper slopes, whereas in La Morra there is more clay and therefore less erosion yielding softer hills. “It gives me a lot of satisfaction when I explain this to people, and I see in their eyes that they understand. It is the passage from simply tasting a wine to putting it in a context.”

The depth of Masnaghetti’s work would not be possible without a genuine love of wine itself. He is a fan of Champagne – but it doesn’t have to be anything fancy. “It’s a beverage of relaxation.” His tastes are classic. He drinks Nebbiolo, Bordeaux – and Sangiovese when he wants something aged. “It gives the most satisfaction of Italian wines when old. You can try wines from the ‘70s and ‘80s that are still in great shape,” he declares, while admitting that he doesn’t have a particular affinity for wines that have been aged. Masnaghetti believes that if the wine is good, it should be drunk. “For me, there doesn’t exist a special occasion for wine. I open a bottle when I want it.” At the table he prizes quality over quantity. “I prefer one bottle, maybe two that are very good rather than the great confusion in your head of what you drank.”

As always with Masnaghetti, it is a sense of order that prevails.

Michaela Morris is an international wine writer, educator and speaker based in Vancouver, Canada. She has worked in various capacities of the industry for 25 years. Besides holding the Wine & Spirit Education Trust Diploma, Michaela is an Italian Wine Expert certified through Vinitaly International Academy (VIA) and leads seminars on Italian wine around the globe. Not surprisingly, her go-to cocktail is a negroni.