In June 1839, a writer for The Bangor Whip newspaper described a “Virginia barbecue” to readers in Maine. Anticipating that a northern U.S. audience would be unfamiliar with this southern U.S. food tradition, the writer tapped “[a] friend, who is a native of Virginia,” as an authoritative source. While describing the logistics for putting on a barbecue, the Virginian noted: “On the previous day, some favorite negro man, of reputation for skill and experience in the business, is sent up with his assistants, who proceed to make a kiln or pit of stones . . . . “ This Virginian’s observation was not an isolated example. Many newspaper articles and diary entries in the 1800s have underscored his essential point that African Americans, whether enslaved or free, were barbecue’s principal cooks.

This wasn’t always the case. In the 1500s, indigenous peoples in the Americas were barbecue’s earliest cooks. By the late 1600s, the culinary foundation laid by Native Americans in Virginia was combined with the culinary techniques and traditions of enslaved Africans and European colonists. A trial-and-error pro-cess created what would eventually be called “Virginia barbecue,” “southern barbecue,” and “pit barbecue.” Due to a failed attempt at mass enslavement and a nearly successful genocide, European colonists transitioned from en-slaved Native Americans to enslaved African Americans for barbecue cooks.

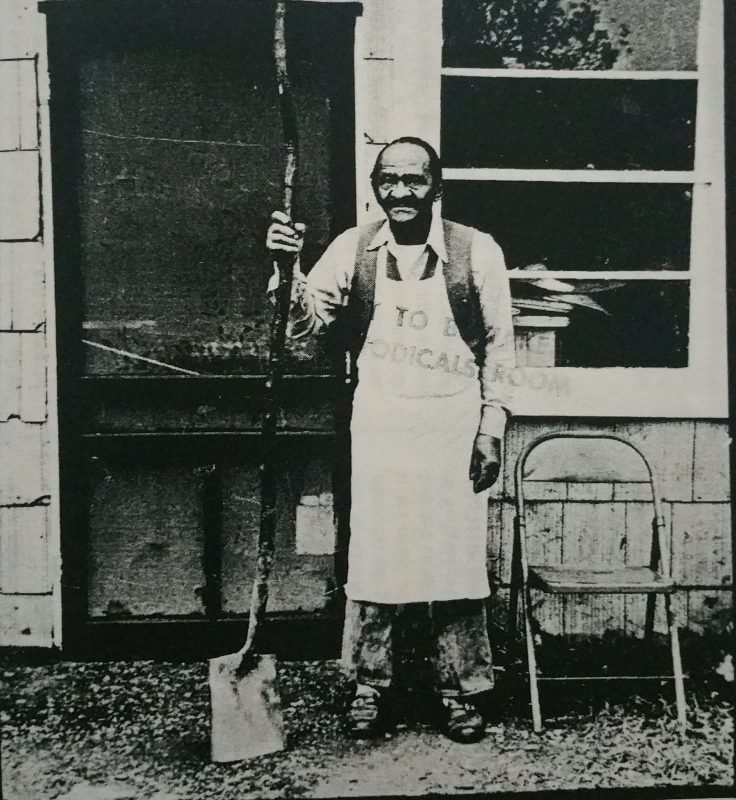

For most of U.S. history, a barbecue in the South was a Black experience from start to finish. Why? Because preparing traditional southern barbecue was very labor intensive. Someone had to clear the rural area where the barbecue would take place, chop down trees and burn that wood into coals, dig a trench, fill that trench with the burning coals, butcher, dress, cook, and season whole animal carcass-es (usually cows, pigs, or sheep), maintain a separate fire to replenish the coals, prepare, and serve gargantuan portions of meat, side dishes, desserts, and beverages. Before they themselves could eat, enslaved African Americans entertained the white barbecue attendees by singing and dancing. Given the racial dynamics of the antebellum South, enslaved African Americans were tasked with mostly uncompensated, heavy labor. Wherever slavery spread to from Virginia, barbecue soon followed.

Barbecues, as social events, started off as small gatherings of family and friends. Some-times these gatherings could be a little raucous as attendees played games and shot guns while copious amounts of alcoholic beverages were consumed. Barbecue became the perfect party food for large gatherings throughout the South because it was scalable. As long as there was enough land, enough food, and enough free or enslaved labor, thousands of people could be fed and a large amount of cooking equipment wasn’t needed. There’s a reason that you don’t hear about fried chicken dinners for 10,000 people happening in the nineteenth century, but you do for barbecue. Politicians and preachers figured out pretty early on that a free barbecue was a great way to attract a big crowd and persuade them to do something you want whether that was getting votes or joining a church’s congregation. In time, barbecues, as a social event, became an important part of civic life that marked special occasions from holidays to the completion of important public projects.

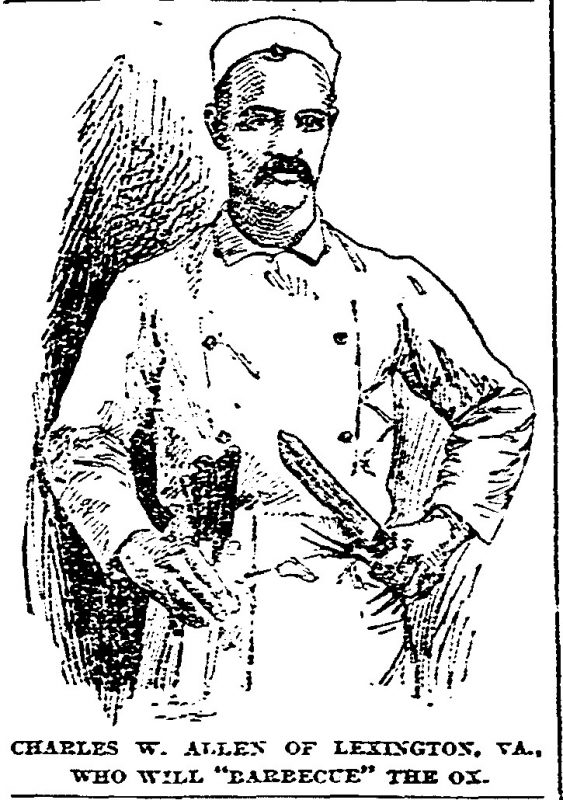

After Emancipation, enslaved African Americans’ prominent role in barbecue didn’t wane. Barbecue remained a vital community celebration, and African Americans with barbecue expertise were recruited and brought to every corner of the nation by boat, stagecoach, and train to give a salivating public a taste of authentic southern barbecue. From the Civil War’s end through the 1880s, it’s hard to find examples of barbecue for any occasion that wasn’t prepared by Black cooks.

Don’t think for one moment that African Americans solely barbecued for others. During slavery, barbecue was a beloved food on weekends and special occasions when the plantation work schedule slowed and there was enough time to do this specialized cook-ing. Cooking a whole animal demands a crowd, so barbecue reinforced social ties, provided a venue for sharing information, and built community amongst enslaved African Americans. In fact, some of the most potent, yet ultimately unsuccessful, slave rebellions were planned during African American-only barbecues. Some pro-slavery whites tried, and failed, to ban such barbecues because of the potential threat to the slave regime. After the Civil War, barbecue was a regular part of African American church summer events, Emancipation celebrations, and political rallies. With all of the barbecuing happening, a large number of African American cooks developed and honed a coveted and marketable skill. That skill created effective southern barbecue “ambassadors,” who migrated to other parts of the country. In their newly adopted homes, they often kickstarted that community’s barbecue scene, especially when it came to restaurants.

A big turning point in U.S. barbecue culture happened in the 1890s. More white men got involved in barbecuing, and they got significant media attention even though they still relied heavily on African American labor. In the early decades of the twentieth century, millions of Black and white southerners moved to urban areas throughout the United States, and they brought barbecue with them. According to Robert Moss, Southern Living magazine’s barbecue editor, the culinary shift brought on by the mass migration spurred an intense period of barbecue innovation. Before then, barbecue was fairly standardized by cooking whole animals directly over a pit dug in the ground and filled with burning coals. That type of cooking was more challenging in an urban context given space constraints and public health regulations. Ultimately, more cooks, especially those new to barbecue, started cooking smaller cuts of meat like pork shoulders, spareribs, and beef brisket. They built, and barbecued on, artificial pits made of concrete or metal in enclosed buildings. This development made barbecue a food available all year for several days of the week, instead of primarily on weekends and special occasions. Hordes of barbecue restaurants opened across the U.S. in the 1910s and 1920s, many of them operated by whites.

African American barbecuers, who had been traditional barbecue’s standard bearers, adeptly adjusted to the new culinary terrain. Black cooks remained strongly associated with the major regional barbecue styles that flourished during this time. Here’s a quick tour of those styles, and for our purposes, I’m just going to focus on the meats because I could spend a lot of time just talking about sauces, side dishes and desserts. In Virginia and the Carolinas, whole hogs and pork shoulders are the starring attractions. In the Deep South states of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi, chicken, pork shoulders, and pork spareribs are favored. In Tennessee, it’s a mix of whole hog barbecue in parts of the state, and spareribs and pork shoulder sandwiches in Memphis. In Kentucky, lamb is a barbecue menu mainstay, but sliced pork shoulder steaks are also common. Further north, on the south side and west side of Chicago, chicken, pork sparerib tips, and spicy sausages called “hot links” get top billing. Kansas City barbecue restaurants feature an eclectic menu of chopped, sliced, or the charred “burnt ends” of beef brisket, chicken, hot links, lamb, pork shoulder, and pork spareribs.

Finally, we get to Texas which has a few distinct styles within the state. Texans in the central and eastern part of the state both like chopped or sliced beef brisket, pork shoulder, pork spareribs, and various types of sausages with some slight variations in the cooking process and presentation. Southern Texas has a long-standing Latino tradition where meat such as a cow’s head (cabeza), goat (cabrito), and lamb (barbacoa) are cooked underground in an earth oven. Whatever form barbecue took, Black cooks were often the ones in their community who gave customers their first, and on-going, tastes of authentic southern, or pit, barbecue. Running a barbecue restaurant was one of the most lucrative businesses for Black entrepreneurs, and they made the most of it.

Unfortunately, starting in the 1990s, the culinary legacy of African Americans gradually diminished or was completely erased in the media. The cooks who get celebrated now are primarily white men, and that’s mainly because it’s white-dominated media who often decide which food stories get told and who gets put in the spotlight. When people with a growing interest in barbecue wanted to know what this particular type of food is and where to get the good stuff, white dudes were presented as barbecue experts even though many Black barbecuers could have been selected.

Don’t despair! I don’t want to end on a bad note. Change is coming. Barbecue competition shows on television now include more Black contestants and the American Royal Barbecue Hall of Fame in Kansas City, Missouri has gone from one African American inductee to several in the past few years. Rodney Scott, an award-winning barbecuer based in Charleston, South Carolina recently published a cookbook . . . the first cookbook published by an African American barbecuer in three decades. Other Black barbecuers have books on the way. Though fewer Black-owned barbecue restaurants exist today than three decades ago, the Black barbecue scene still thrives in backyards, church gatherings, family reunions, food trucks, parking lots, public parks, and roadsides. Thankfully, we’re seeing a restoration of African Americans to the center of the American barbecue story. That’s worth celebrating . . . with some barbecue!

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2021 print issue of Quench Magazine.

Adrian Miller is a food writer, recovering attorney, and certified barbecue judge who lives in Denver, Colorado. He served as a special assistant to President Bill Clinton with his Initiative for One America – the first free-standing office in the White House to address issues of racial, religious and ethnic reconciliation. Adrian’s first book, Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time won the James Beard Foundation Award for Scholarship and Reference in 2014. His most recent book, Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbecue, was published in 2021. Adrian is featured in the Netflix series High on the Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America. His go-to restaurant that never disappoints is Georgia Brown’s in Washington D.C.