Sure, it’s cliché to say that a river of wine flows through history – but it’s hardly incorrect. After all, most world-changing human endeavours haven’t been solidified over glasses of milk.

Skirmishes between Great Britain and France dating back to the sixteenth century saw sherry become one of the most important Iberian exports to England as the flow of French wine dried up. There’s plenty to be found in the Quench archives detailing the history and production of sherry and its various styles, and the development of the industry – even tips for enjoying it. My focus here will be where the sherry industry stands today, and where it may go in the future.

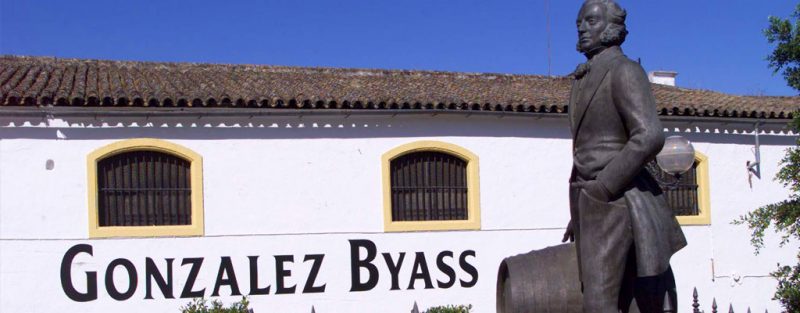

To provide a bird’s-eye view of the Jerez vinous landscape, I tracked down Victoria González-Gordon López de Carrizosa, 5th generation of the González Byass family and the company’s chief sustainability officer. With origins dating back to 1835 – and solely owned by the family since 1988 – González Byass is one of the world’s most recognized and important sherry producers. It has weathered the ups and downs of the industry, and faced and met the challenges the years have brought. In other words, it’s basically a time capsule of the sherry region, its industry, and its wines.

“Since the sherry glory days of the 1970s and 80s, producers have adapted significantly to the changing demands of international markets,” Vicky confirms (and I’m going to use the less formal first name rather than repeating González-Gordon López de Carrizosa over and over. It’s a word count thing, okay? Thanks). She says that although volume sales are a cornerstone of industry success – particularly in traditional markets like the UK and Holland, González Byass and other sherry bodegas have shifted focus from volume production to premium products.

“González Byass has been a prime mover in the category when it comes to innovation; in line with its move to making much more premium sherry,” Vicky reveals, noting that “the release of small-batch sherries such as Tio Pepe En Rama, or the Las Palmas Collection have done a great deal to attract top-end wine aficionados to the category. Equally, vintage and limited release sherries, such as our Finite Wine collection, are engaging top restaurants and retailers, and inviting them to enjoy, sell, and promote the very best sherry wines around the world.”

She also notes that some pretty sweeping additions to geographical and legal parameters have recently been approved by the region’s Consejo Regulador (the authority responsible for ensuring that the regional regulations are observed).

Vicky reports that the modifications introduced include expanding the production areas for where wines can legally be called sherry, allowing more wineries to promote their wines as such. In addition, new grape varieties are being approved for production, responding to the demand for native varieties and those that can adapt to the changing climate. In fact, six new grape varieties will be permitted. These include Beba, Cañocazo, Mantúo Castellano, Mantúo de Pilas, Perruno, and Vigiriega. As with other wine regions, climate change is having a definite impact on the harvest, and while studies are ongoing, it is believed these varieties will respond well to conditions of heat and drought.

To offer even more detailed information to consumers, sherry producers will now be able to indicate a pago – or area – on the label, indicating precisely where the fruit was harvested. Also, the en rama designation will be more strictly controlled. It’s a term you’ll likely see more of as producers of the lighter, drier styes of sherry – fino and manzanilla – look to increase the complexity and individuality of their wines.

En rama essentially means “minimal filtering,” and it harkens back to a time when the impact of flor – the naturally occurring yeast layer that gives these wines their distinctive tang – played a more significant role in the flavour profile of the final wine. In the ‘70s and ‘80s most sherry bodegas applied fairly heavy filtration to achieve consistency and, well, “commercial acceptance” (a nice term for a blander tasting but perhaps nicer looking end product).

Another interesting feature of en rama sherries is that the cellar master will select the final wines to be blended from barrels where the flor is particularly active. Rather than consistency as the end goal, the aim here is for distinctiveness, so you’ll find a bodega’s en rama expressions will vary from year to year.

En rama sherries have only really been made available to a wide consumer base over the past decade or so, but today most of the main players are offering their own versions. It’s an enlightening exercise to compare, say, the regular bottling of Tio Pepe Fino with the Tio Pepe En Rama.

It will be interesting to see how these new regulations, grapes, and styles wash with the end consumer. Sherry – even for the more seasoned wine geeks – has never been the easiest wine to understand, and even industry insiders seem to concede that some of these changes may make an already complicated wine even harder to understand. Regardless, sherry will continue to be an absolute pleasure to drink.