I was sure we nailed it.

A careful selection of the component spirits painstakingly sampled in laboratory pipette measures into a graduated cylinder. The millilitres recorded before the contents added to a beaker. Then swirled and emptied into a waiting tasting glass. The contents nosed to determine the experimental blend’s proximity to the “real deal” — the “control sample” in the other tasting glass beside me. A little heavy on the caramel/honey notes, I judge. A squirt of a smoky malt, and a dollop of another with a grainier/cereal quality to counterbalance.

Smell. Compare.

Getting there … definitely getting there, but still a touch on the heavy side. Just a smidge of a lighter, more neutral sample to tone things down a wee bit.

Smell. Compare.

Ah, okay … so close, but off by just one or two notes. Where’s that component sample with the slightly fruity, pear-like note? Right … a little of that. “Careful,” my blending partner (BP) cautions as I, with a slightly shaking hand, administer but two drops (two drops!) directly into our final amalgam.

Smell. Compare. Smell. Compare. Pass to BP.

Smell. Compare.

“I can’t tell the difference. I think we nailed it!” Pass to a bystander in the crowd who’s been watching all this go down. “Wow. That’s pretty good. You’ve pretty much nailed it!”

Pass to the judge. Smell.

In hindsight, I shouldn’t have even expected I’d be able to replicate the blend that makes up The Famous Grouse Blended Scotch whisky. They say that spirit blending takes the work of both an artist and a scientist. I am neither.

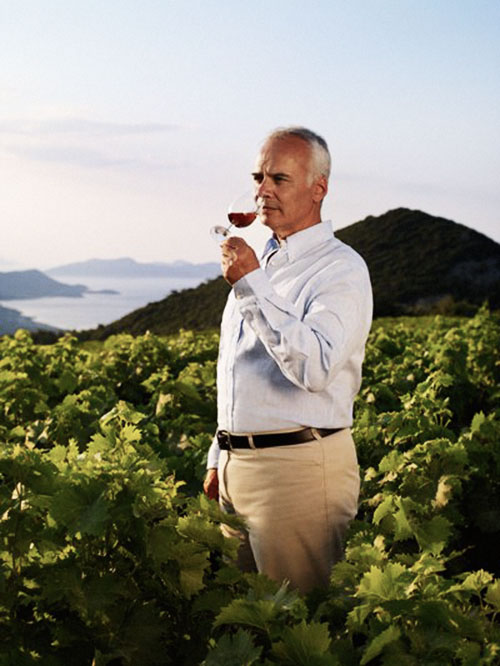

Now, I’ve been subjected to the organoleptically humbling “blending exercise” on several occasions. With the Metaxa Master Blender in sunny Greece. With the Mount Gay Rum Master Blender in sunny Barbados. My first-ever blending exercise (and, as I recall, one of my first ever professional wine events) was trying to duplicate the “recipe” for the German wine Blue Nun [see page ??] in Toronto (where I recall it being at least partially sunny). I’m sure there were more. Most have been mentally blocked, as the mind can only tolerate a finite number of crushing failures.

The Famous Grouse Defeat (henceforth, TFGD), however, was the last pipette (as it were). I will no longer participate in such sadomasochistic “exercises,” no matter how sunny the locale or how gracious the host.

I mean, seriously, even the dreaded “blind” wine tasting offers more opportunities for a possible ego inflating win than a spirit blend-off. “I guessed the colour right!” can, at the end of it all, count as a victory. In any case, it got me wondering as to whether anyone could replicate a spirit blend close to perfectly. (Yeah, yeah, okay … the guy who did come out primo must have done a fair bit better than me. Ditto for the guy who came secondo. And, like, no, I’m not saying the judge could have been bribed or anything like that.)

Consider: the point of the art/science/frustration of spirit blending is twofold. First, it’s to create a sort of liquid gestalt, where the blend turns out to be something magically different than its component parts. The second is to be able to recreate this consistently, day in day out. Most spirits are, in fact, blends. And whether you’re blending whisky, brandy, rum, or tequila, you’ll be shooting for a common goal (though you may go about it somewhat differently).

“The common objective [in blending] is to obtain a product that conforms to a standard,” confirms Karina Sanchez, Global Brand Ambassador for the tequila producer Casa Sauza. “For a specific [type of] spirit, the blending process has unique details related to customs and legal constraints, production and warehousing processes, approval criteria, and so on.”

These blends are typically closely guarded secret recipes, sometimes passed down from hand to hand. Could someone who’s not a part of the covenant of the Master Blender/Knights Templar/Masonic Orders in general, ever be able to duplicate a successful blend?

Maybe it isn’t possible. Maybe trying to replicate a blend is a mug’s game.